Royal College of Art, Gulbenkian Galleries, Kensington Gore, 19th July 2010

A major retrospective exhibition of the work by one of the most influential graphic designers of the 20th century.

I first became interested in ROMAN CIESLEWICZ's work when researching collage artists for my dissertation. I found that much of the work I could relate to my own collage work, and I admired the precision and composition of his work, which is predominantly hand made. Cieslewicz is a polish designer and I had come accross his work when looking at polish poster design, only now have I been able to put the work to a name.

Plakatodrom (Welcome to the Posterdrome)

Plakatodrom was Cieslewicz's name for Poland, describing the country as 'the largest testing ground of the poster in Europe.' Film posters in the West were often vehicles for Hollywood stars, however within Polish poster design, the same films could be promoted but with a personal even idiosyncratic style.

Cieslewicz belonged to the second genration of 'the Polish poser School' ( a loose alliance of modernist designers) He began his career in the 1950's when communist censorship was being relaxed and experimentation was welcomed. Cieslewicz gained a reputation for extraordinary surreal images. I have been influenced by Cieslewicz's posters, whilst devising posters for my current summer project.

"A Poster is an idea. This is what matters. An idea can excite, can be intriguing... it was marcel Duchamp who said "an image, which does not provoke is unworthy" and he was right. We are surrounded by images. We are hit by tens of thousands of advertisements every day. We may or may not accpet them, The image is not neutral. It cannot be. It must shout, it must intrigue, it must do something which enables us to think.' - Roman Cieslewicz, 1978.

Ty i Ja was first published in 1959. Cieslewicz was the first art director of 'Ty i Ja' which translates in English to 'You and I.' Under Cieslewicz's art direction the magazine had a remarkably idiosyncratic nature. The magazine featured advertisements (designed by Cieslewicz) for products which were almost impossible to obtain and fashion spreads were 'borrowed' from 'Elle' and 'Vogue', and distorted by the likes of butterfly wings and irreverant doodles.

The Double Life Of An Art Director

After Cieslewicz moved to Paris in 1963 he embarked on an impressive career in periodical publishing and advertising. Working for the likes of Vogue and Elle, the very magazines, which he had borrowed imagery from for 'Ty i Ja.' He was also made art director of MAFIA, a celebrated advertising company established by Denise Fayolle and Maime Arnodin. Cieslewicz worked for corporations and commercial chains alongside photographers, Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin.

The late 1960's were angry years in France. In contrast to his commercial work, Cieslewicz created powerful covers for the art magazine 'Opus.' Infected with radicalism, Opus, protested against the 'Alice in Wonderland' world of advertising and celebrated the vibrant life of contemporary Cuba and the Soviet Union in the 1920s.

In the 1970s Cieslewicz became a freeland designer and illustrator. His double life is summed up by this quote 'I work for institutions who pay me, in order to be able to work for those who have no money.'

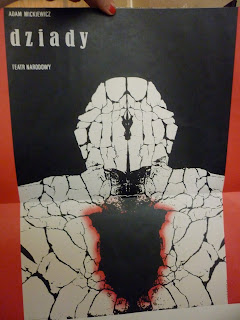

Forefather's Eve (Dziady), 1967.

This poster has become an iconic image in the history of The People's Republic Of Poland.' Designed to promote Adam Mickiewicz's nineteenth century poetic drama, Forefather's eve (Dziady). the poster is a symbol of the simmering frustration of Soviet Controlled Poland.

The Photocollages

One aspect of Cieslewicz's work, which particularly struck me was his photocollages. After 1984 Cieslewicz simplified his collages,yet still linked humour with anguish and reality with fiction to 'trigger' perception and 'sharpen the eye.' I particularly enjoy 's use of renaissance imagery, combined with contemporary imagery. This not only resonates with some of my own collage work but also amuses the viewer creating a provocative and playful composition

Playboy de la Sixtine (Playboy of the Sistine chapel), 1982

Mirror Worlds

a series of 'centred collages', which play with lines of symmetry to create mirror images. What is missing or obscured is as significant as what is visible.

A Constructivist in Paris

Cieslewicz collaborated with the Centre Georges Pompidou to explore the art of european art in the 1920s, Cieslewicz proved remarkably skilled at reinterpreting the graphic language of consructivism in the manner of Alexander Rodchenko.

The Politics of the Image

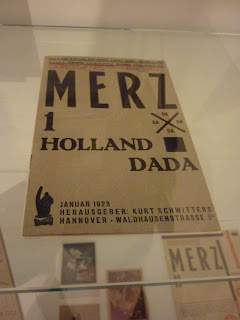

Cieslewicz described his work as a form of 'Visual Journalism'. He created an entire series called 'Pas de Nouvelles - Bonnes Nouvelles (No News is Good News). During a stay in hospital Cieslewicz followed the news and noted down imagery, which he later cut out from the press. Combining grainy news photographs with short epigrams, Cieslewicz pointed to the violence of the images. Press imagery seems to be an invaluable resource for collages artists (pre computer age). Many Berlin Dada artists such as Hannah Hoch, admired and ridiculed press material. Perhaps the use of this medium is an effective way to create on the pulse work, which comments on or distorts the current.

Review:

A wall collapses here, a door upends over there. An egg-shaped abode hides a womb-like interior and there's a creeping suspicion that all is not well at home. 'The Surreal House' is an ambitious and rewarding, if necessarily sinister peek into some of the most bizarre dwellings imaginable - its scope grand enough to include art, architecture, film and photography, while its atmosphere close and cloying enough to induce moments of sheer terror and genuine delight.

Film emerges as the most powerful medium in 'The Surreal House' with Jacques Tati's hapless 'Mon Oncle' and Jean Cocteau's 'La Belle et La Bête' contrasting the ridicule of modern living with a wildly romantic fairy tale fantasy - but both require that you watch them in their entirety in a specially built cinema. The show proper opens with Buster Keaton's famous slapstick sequence from 'Steamboat Bill Jr', in which his own house is blown down around his ears, and leads you to the objects contained within the Barbican's custom-built structure. Yet neither a pair of Duchamp's darkened French windows (called 'Fresh Widow') or his cheeky rubber-foam boob in place of a doorbell, give any real clues as to what's inside. The initial shock then comes when presented with a blacked-out bathroom, where Rachel Whiteread's sepulchral resin cast of the space under the tub greets visitors with our own grubby mortality.

A spyhole refuses to reveal the secrets behind Sigmund Freud's front door, but the meister of repression's office chair is here in his stead. Alas, we soon get Freud's massively overused theory of what makes a surreal house a home for nasty memories practically shoved down our throats. His notion of the unheimlich, or unhomely, is appropriate in this context, but is little more than paying lip service to art-speak cliché - it's now shorthand for anything a bit 'strange' in contemporary art.

The earliest spaces to mimic Freud's ideas were the original and best surreal houses: André Breton's elegant apartment shelves appear on camera, filled with a curio collection of the highest order (shamefully auctioned off piecemeal in 2003) and none other than the 'Great Masturbator' himself, Salvador DalÌ, created some of the most outlandish and unreal environments, not least his 'Dream of Venus' pavilion created for the 1939 New York World's Fair. Trying to marry DalÌ's paintings with later architecture is a major mistake, however, especially in the nonsensical pairing of his 1937 'Sleep' with Rem Koolhaas's villa on stilts from 1991, chiefly because it does the overarching theme no favours at all.

Everything takes a surreal turn for the better when the curators play, not at intellectual ping-pong or tenuous connect-the-dots, but at impressive interior design. A crumpled, clanking piano by Rebecca Horn hangs from the parlour ceiling, a locked door guards an artist singing as he wipes on the toilet, a lonely window stares down on an unloved Sarah Lucas mattress in the bedroom, while Jan Svankmajer's troubling nursery of animated toys is a welcome burst of colour in an otherwise monochrome world. Not every allusion works - Maurizio Cattelan's sorely punished mannequin boy with pencils stuck through his hands is no more than a lame joke, as is Edward Kienholz's waiting room, in which the armchair resident has long ago been reduced to a dusty skeleton. Without the drama of the house motif to its layout, the upper floor suffers badly by comparison, although a trio of Joseph Cornell boxes significantly ups the dwindling masterpiece quota.

Thankfully, the numerous female artists in the exhibition are not unfairly included here as inherently domestic beings or confined by any stereotype that they're unable to control their natural homemaker's urges. In fact, the most acute representations of domicile distress by Louise Bourgeois and Francesca Woodman effectively consign their male counterparts to the basement of the genre, although the last word goes to Russian auteur Andrei Tarkovsky and to his chosen form: art house film. The end sequence to Tarkovsky's 'The Sacrifice' of 1986, in which the protagonist burns down his house, thus freeing himself from the enslavement of nostalgia that his cups, dressers and tables inflicted upon him on a daily basis, is a telling reminder of what alienating, divisive and constrictive environments we live in. 'The Surreal House' is ultimately a metaphor for our unconscious mind. It's filled with knick-knacks and memories - some important, others not - but it's when something in there snaps or goes missing that the comfort and homeliness we crave lay bare that much darker place.

Review:

A wall collapses here, a door upends over there. An egg-shaped abode hides a womb-like interior and there's a creeping suspicion that all is not well at home. 'The Surreal House' is an ambitious and rewarding, if necessarily sinister peek into some of the most bizarre dwellings imaginable - its scope grand enough to include art, architecture, film and photography, while its atmosphere close and cloying enough to induce moments of sheer terror and genuine delight.

Film emerges as the most powerful medium in 'The Surreal House' with Jacques Tati's hapless 'Mon Oncle' and Jean Cocteau's 'La Belle et La Bête' contrasting the ridicule of modern living with a wildly romantic fairy tale fantasy - but both require that you watch them in their entirety in a specially built cinema. The show proper opens with Buster Keaton's famous slapstick sequence from 'Steamboat Bill Jr', in which his own house is blown down around his ears, and leads you to the objects contained within the Barbican's custom-built structure. Yet neither a pair of Duchamp's darkened French windows (called 'Fresh Widow') or his cheeky rubber-foam boob in place of a doorbell, give any real clues as to what's inside. The initial shock then comes when presented with a blacked-out bathroom, where Rachel Whiteread's sepulchral resin cast of the space under the tub greets visitors with our own grubby mortality.

A spyhole refuses to reveal the secrets behind Sigmund Freud's front door, but the meister of repression's office chair is here in his stead. Alas, we soon get Freud's massively overused theory of what makes a surreal house a home for nasty memories practically shoved down our throats. His notion of the unheimlich, or unhomely, is appropriate in this context, but is little more than paying lip service to art-speak cliché - it's now shorthand for anything a bit 'strange' in contemporary art.

The earliest spaces to mimic Freud's ideas were the original and best surreal houses: André Breton's elegant apartment shelves appear on camera, filled with a curio collection of the highest order (shamefully auctioned off piecemeal in 2003) and none other than the 'Great Masturbator' himself, Salvador DalÌ, created some of the most outlandish and unreal environments, not least his 'Dream of Venus' pavilion created for the 1939 New York World's Fair. Trying to marry DalÌ's paintings with later architecture is a major mistake, however, especially in the nonsensical pairing of his 1937 'Sleep' with Rem Koolhaas's villa on stilts from 1991, chiefly because it does the overarching theme no favours at all.

Everything takes a surreal turn for the better when the curators play, not at intellectual ping-pong or tenuous connect-the-dots, but at impressive interior design. A crumpled, clanking piano by Rebecca Horn hangs from the parlour ceiling, a locked door guards an artist singing as he wipes on the toilet, a lonely window stares down on an unloved Sarah Lucas mattress in the bedroom, while Jan Svankmajer's troubling nursery of animated toys is a welcome burst of colour in an otherwise monochrome world. Not every allusion works - Maurizio Cattelan's sorely punished mannequin boy with pencils stuck through his hands is no more than a lame joke, as is Edward Kienholz's waiting room, in which the armchair resident has long ago been reduced to a dusty skeleton. Without the drama of the house motif to its layout, the upper floor suffers badly by comparison, although a trio of Joseph Cornell boxes significantly ups the dwindling masterpiece quota.

Thankfully, the numerous female artists in the exhibition are not unfairly included here as inherently domestic beings or confined by any stereotype that they're unable to control their natural homemaker's urges. In fact, the most acute representations of domicile distress by Louise Bourgeois and Francesca Woodman effectively consign their male counterparts to the basement of the genre, although the last word goes to Russian auteur Andrei Tarkovsky and to his chosen form: art house film. The end sequence to Tarkovsky's 'The Sacrifice' of 1986, in which the protagonist burns down his house, thus freeing himself from the enslavement of nostalgia that his cups, dressers and tables inflicted upon him on a daily basis, is a telling reminder of what alienating, divisive and constrictive environments we live in. 'The Surreal House' is ultimately a metaphor for our unconscious mind. It's filled with knick-knacks and memories - some important, others not - but it's when something in there snaps or goes missing that the comfort and homeliness we crave lay bare that much darker place.